This is part II in my mini-series on New Zealand which features our bid to ski Mt Tasman’s Syme Ridge amid some furious New Zealand weather that had us pinned down in Plateau Hut for 36 hours. If you missed Part I – Darwin and Silberhorn, you can read it here.

Back at the hut, we followed the time honoured post ski ritual of eating and sleeping, attempting to replenish the essentials we were lacking, in preparation for our next objective. For the next 36 hours, the wind shook the hut and howled like a banshee, frequently waking us from our slumber. We used pee buckets inside the hut to avoid the risk of opening the steel barred door and potentially not being able to close it against the sheer force of the wind. A significant amount of snow was forecast, but it was difficult to predict how much would accumulate and how much would be blown away in the storm. Our waking hours were spent cooking, eating, and joking with one another while trying to stay warm, as the cold seeped into our feet and up our legs, often convincing us to retreat into the warmth of our sleeping bags once more.

One of my main goals for the trip was to ski the Jones Route on the East Face of Cook. With the cold weather maintaining a winter snowpack, the series of steep, exposed ramps promised good skiing, similar to the Mallory route on the North Face of the Midi, albeit with a 1,500-meter ascent to start the day and the use of lighter ski mountaineering equipment. I anticipated that the new snow would settle nicely under the sun tomorrow, making it a great opportunity for the day after that. After an injury forced me to withdraw from the team that made the first descent of the Caroline, I felt that tackling this more challenging route would help make up for that disappointment. However, my intuition suggested I wasn’t the only one aiming for this line, so not wanting competitive spirit to cloud our judgment and lead to a preemptive strike, I discussed the plan with Christina, and we agreed to team up for it the day after tomorrow. With the business side concluded, I went off for a siesta.

After my refreshing nap, I strolled into the kitchen, where an unsettling, morbid atmosphere hung heavy over the group like a thick mist. Still groggy, I struggled to grasp the source of the tension when I saw Beau abruptly leave the room, his expression clearly torn with distress. Christina, her voice low and serious, filled me in on the devastating news: Beau’s dear friend, Mike Gardiner, had suffered a fatal fall on Jannu East. Feeling a pang in my chest, I made my way into the hall, where I found Beau seated alone, his gaze fixed on the floor, lost in profound thought. I joined him in silence for a moment, grappling with my inability to find the right words to convey my condolences. We were both well-acquainted with the exhilarating highs of mountain life, but we were also painfully aware of its darker, haunting side—grappling with the agony of such loss. I eventually left Beau to retreat into his thoughts, knowing he could draw strength from the room full of friends ready to support him during this painful time.

As evening fell, Beau made the heart-wrenching decision to spend the next couple of days glacier skiing, his thoughts consumed by the tragedy that had befallen his friend. Meanwhile, Christina and Gee expressed their eagerness to ski a new line on the Vancouver Peak whose approach up the Linda engulfed in darkness with overhead threat, and the small hanging face itself, didn’t call to me. Instead, I chose instead to head for Syme, where the ridges provided a comforting sense of security following the fierce storm that had recently passed. The thought of going without Beau felt gut-wrenching; he had often shared his excitement about this line but we both understood that in the unpredictable world of mountaineering where weather, snow conditions, physical and mental preparation, rarely come together, and when they do, the Universe calls to you – Go!

Just as I was resigning myself to going solo, Christina suddenly turned to me and announced that they would join me. The realization that this spot would offer the most aesthetically pleasing backdrop for filming near the hut was likely the catalyst for her change of heart. Energized by the prospect of the trip, I dove into my packing, meticulously arranging my clothes and gear in the kitchen, careful to keep the noise to a minimum so I wouldn’t disturb Beau when I rose at 1 a.m.

Once again, we stepped out of the hut into a darkness so profound it felt as if we were venturing into the depths of space. I began breaking trail, my eyes fixed on a shimmering star above Lendenfeld, guiding us through the abyss. We soon reached the crevasse field, where Gee took over navigating us skillfully over the icy Bergshrund before we transitioned to crampons. The frigid wind relentlessly clawed at our hands and feet, urging us to move swiftly up the apron to generate warmth. As we climbed higher, the howling wind intensified, stripping away any remaining heat. Exiting the protective confines of the couloir, we were confronted by the full force of the icy blast. I paused for a moment, fumbling to put on my heavy down jacket and mitts, feeling their comforting insulation against the biting cold.

Ascending further was a grueling effort; the powder was so deep it reached up to my thighs. Forward progress required me to pack the snow in front of me with my knee before being able to step up. Finally, we reached the top of the Diamond. Just as Gee dropped his pants to take a toilet break, and without warning, a monumental rumble shattered the stillness—a massive avalanche of snow cascading down from the darkness above us. My heart raced, and I imagined Gee’s surprise as he hurriedly rectified his situation. Just as quickly, we reassured ourselves that we were safe on the shelter of the ridge, despite the tumultuous chaos above.

As we pushed upward, our progress was steady but slow, each step a reminder of the struggle ahead. The southerly wind whipped fiercely across the ridge, its biting chill forming delicate rime ice around our eyes and under our noses. My left foot, trapped in its icy coffin, protested with a numbing ache, forcing me to pause frequently to unbuckle my boot and wiggle my toes within the confines of the shell. Just as I did, the sun began to peek over the horizon, casting a warm, golden light upon the snow-covered peaks. We turned toward the light in reverence, basking in the gentle rays that melted away the night’s chill, as the mountain transformed into a canvas painted in soft pink hues at dawn’s early embrace.

Now the sun peered over the horizon and we turned to greet it in worship, welcoming its warming rays, as once again the mountain was painted pink in the avant glow of dawn. After bring confined to the space limited by our head torches’ illumination, the stunning landscape unfurled before us, revealing the vast expanse below. The wind blasted snow across the ridge, the Grand Plateau far below, and beyond mountainous islands floating in a sea of clouds, whilst the horizon was ablaze as the sun climbed ever higher. We continued up, filled with the otherworldly feelings of being on a Himalayan Giant.

We reached the area of glacial ice we had seen from the hut, gleaming like glass against the rugged mountainscape beneath us. This ice revealed an remarkable cave feature, forming a natural tunnel straight through the ridge. As we climbed upward to the right, I began to clear away the soft slab of ice that lay over the ice in order to place my axe securely. Thankfully, It wasn’t long before we found ourselves back on firmer, more reliable snow.

Approaching the summit of Syme, we decided to move to the north side of the ridge, which shielded us from the biting wind blasting across the crest. Just as I approached the plateau where Syme and the North Ridges converge, the unthinkable happened; my boot punched through the seemingly solid surface and I started to fall down, my body sinking into a hidden crevasse that swallowed me up to my waist. In my initial struggle to regain my footing, I only made the situation worse, but after some more calculated movements, I managed to pull myself free. I quickly shouted down to Gee, warning him to proceed with caution.

Once on the plateau, we paused for a moment, taking in the breathtaking panoramic views that stretched before us: the majestic pristine glaciers sparkling under the sun, with the distant Tasman Sea shimmering like a sheet of blue glass. It was an awe-inspiring sight that made the suffering of our ascent all the more rewarding.

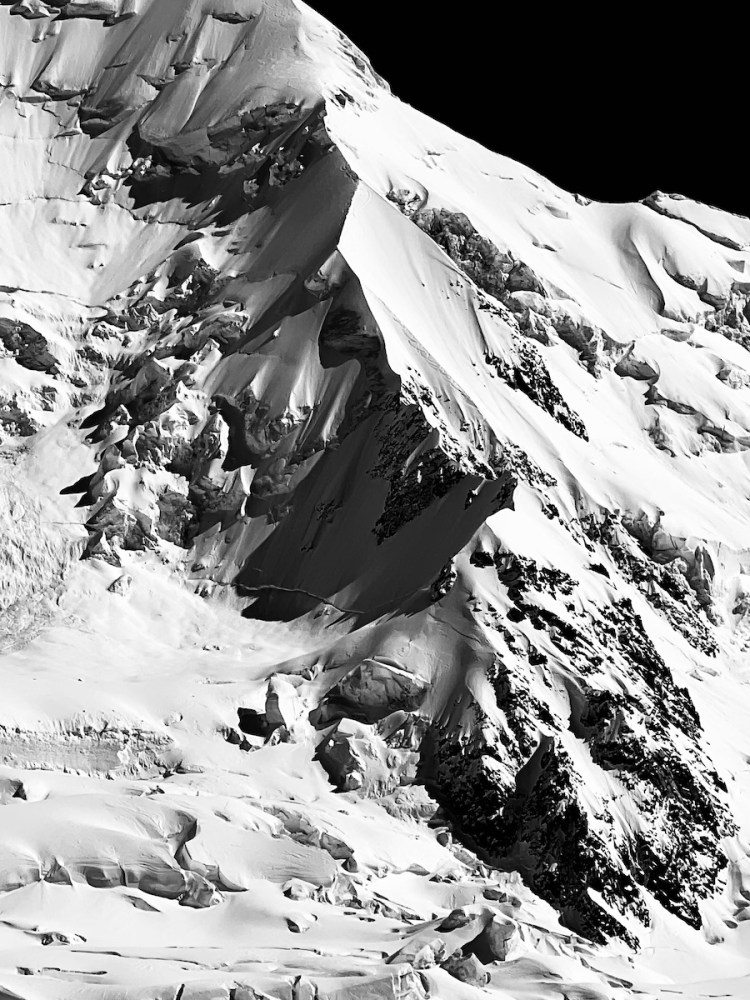

A thrilling pulse of excitement coursed down my spine, igniting every nerve in my body. After years of anticipation, I was finally on the verge of fulfilling a long-held dream: riding Syme. With each sweeping turn, we glided down the initial slopes of wind-pressed powder in between patches of glistening ice. Gee, deftly zagged around the ice cave pitch, to get to the top of the diamond face. He then chose a conservative line, launching down the right spine in a series of hop turns while leaving the diamond for Christina and me to carve some freeride lines.

From my position, the steep face below was a mystery, hidden from view. I picked up my poles and slid leftwards onto the face, feeling gravity of the void below slingshot me across the fall line across the fifty-degree powder, the immediate rush of adrenaline coursing through my veins and in that instant, I slipped into that coveted flow state, losing myself in moment. —a feeling like no other, surfing on immaculate silk, time slowing, ultimate awareness, one turn linking to another. Finally catching sight of the guys on the ridge, their excitement within mirrored by their wide smiles andI scrubbed off speed with my skis chattered beneath me, eager not to scare the living daylights out of them coming in hot. The remaining stretches of our descent were less consequential, yet filled with an exuberance that electrified the air around us. We raced through the choke and down the glacier, where Beau and Mathurin awaited us, their camera lenses capturing the beauty of the moment.

As we shared hugs, an incredible sense of contentment washed over me, happy to have skied a dream line in a modern, progressive style. After grabbing some food, I fell into a deep sleep, allowing my body to recover from the day’s excursions and exposure to the cold. That night, we would set out on a more ambitious outing – to attempt the unskied Jone’s Route on Aoraki /Mt Cook’s East Face before a windstorm arrived.